Honestly, this review has taken me so long to write because I have no clue what to make of this movie. I’m not sure this will be much of a review, inasmuch as a scramble to try to figure out what meaning I can garner from the movie after so much time has passed.

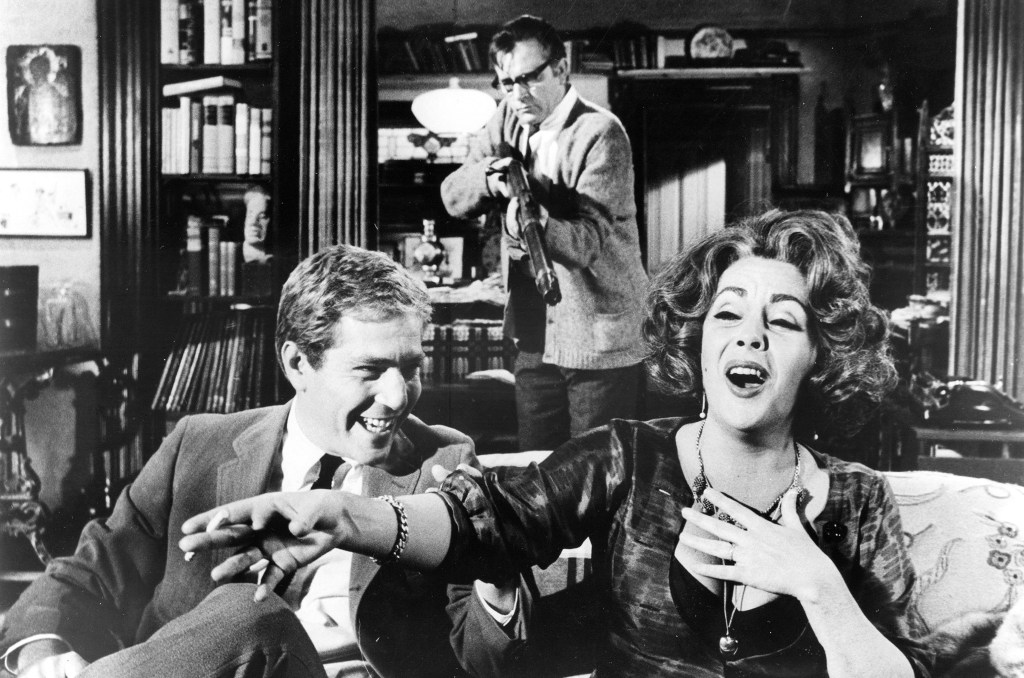

In the movie, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton play Martha and George, a married couple. He’s a professor and she’s the university president’s daughter. They invite a younger couple over after a social event. Things spiral from there, with Martha and George constantly bickering at each other and Nick and Honey trying their best (and failing) to stay out of the line of fire.

My immediate, unfiltered thoughts on gender in this film is that so much of it revolves around childbearing. Both of the women experience issues surrounding childbearing–Martha by accident, Honey on purpose. Martha generally possesses the most undesirable qualities in women. She curses. She drinks. She’s loud. She wears tight pants (pants!). She has a sexual appetite. She flirts with the younger man, eventually sleeping with him. Oh yeah, and she can’t have a baby.

I don’t mean to say that Martha is a bad character, or an unsympathetic one. But I think there’s a deliberate correlation here with her personality and her inability to bear kids. We never really find out whether it’s Martha or George’s infertility causing the problem, but it’s all about Martha, in the end. It’s Martha who first brings up their pretend son, it’s Martha who tenderly recounts his nonexistent birth and childhood, and it’s Martha who admits to being afraid of Virginia Woolf as George sings to her at the end of the film. These moments, and the lack of parallel emotional depth from George on the issue of their son, suggest that this is a deeper, more complex problem for Martha than it is for him. Her womanhood is directly in challenge because she cannot have a child and is therefore unable to pursue motherhood. The crassness is a cover up.

In short, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf is about the emasculation–so to speak–of woman.

The literal definition of emasculation is to castrate a man, but the way its most often used is to deprive a man of his strength or power. In pop culture, male figures are emasculated when they are made fun of for being feminine, which implies they’ve “lost” their masculinity. There’s no exact opposite of “emasculation” which can be applied to women. After all, in a society where masculinity and power are such closely linked concepts, who would be afraid of losing weakness (femininity)? The closest I could find was a scholar in 1986, who used “defeminate”, but even that seemed only to describe an equivalence in terms of sexual satisfaction, or lack-there-of (a woman is defeminated when a man denies her sex). But for the purposes of this article I’ll use “defeminate” as an opposite of “emasculate” to suggest that the crux of femininity is lost when a woman deviates from gender norms. When she deviates, she loses her femininity, and is therefore defeminated.

As a symbolic figure, Virginia Woolf is a critical piece of feminism’s record in literature. She wrote about feminist themes that dated back far before the women’s movement, both in personal letters and her fiction, and was revived as an icon for that work later on. But Virginia Woolf’s complicated ideas about gender isn’t examined textually in the film; rather, the characters merely sing her name every few scenes using the refrain “Who’s afraid of Virginia Woolf.” Woolf becomes a ghost which haunts the two sets of couples throughout their time together. Given that the movie was made in the 1960’s, in the midst of the women’s movement (which notably focused on issues like sex and birth control), Virginia Woolf acts as a symbol, brought through time, to represent women’s liberation for the purposes of this film. The Ghost of Women’s Lib Present, if you will. Virginia Woolf’s legacy hangs unspoken to suggest the background presence of women’s social change even as our protagonists have seemingly unrelated adventures.

The generational gap between Martha and Honey comes into play here. Women, even now, are geared towards motherhood by everything from helping out around the house more as children to the downright unnecessary amount of baby dolls that exist to allow little girls to play mom. These things aren’t accidental. They are part of a purposeful, centuries-old system that convinces women that child rearing is their key to fully participating in society. (Hint: the system is Patriarchy.) This has somewhat changed over the generations, helped in a big way by women’s liberation, which brought multiple ways to see oneself as a woman into the forefront of our society’s consciousness. Though they are usually problematic “do it all” kind of stereotypes, the ads that tout working women as perfect idealized symbols of femininity are a result of a social movement that sought to define the experience of womanhood separately from reproductive capabilities. In short, women’s liberation gave rise to different conceptions of womanhood, separating it somewhat from child rearing.

Martha represents the average woman who came up in this pre-liberation period. Martha is “defeminated” when she’s unable to have a child–she’s unable to fulfill her “purpose” as a woman.

Honey, meanwhile, chooses not to have a child. It’s revealed that the hysterical pregnancy that Nick married her for was actually an abortion, which she elected to get without his knowledge. Honey had a choice to make, so she took control of her body and made it. This is a choice a post-liberation woman (aka, a woman with multiple ideas of what womanhood means) can make without the same anxiety that overwhelmed Martha. She took advantage of a political landscape and ideology more favorable to “my body, my choice” mantras, and acted.

OK, that’s kind of assertive coming from sweet, stupid, “never mix, never worry” Honey. But the generational gap between the women lends itself to an analysis that examines their ages in relationship to the changing identity of the ideal woman in this period. One which Virginia Woolf has come to be a symbol of, even if she didn’t live during this time.

And, after all is said and done, who is really afraid of Virginia Woolf, and of what she symbolizes for women? Women like Martha are afraid. Women who are at a point in their life where changing is harder than just living through the evil they know. The woman whose concept of self has been so tied to motherhood and reproduction she and her husband invented a son just to deal with the pain of their infertility–that’s the woman who’s afraid of what comes next.

It would be a little too simple to proclaim that the movie lays the blame for Martha’s defemination at feminism’s feet. In fact, you could make the case that Martha represents a shallow vision of women’s liberation herself: She wears pants and is hypersexual (masculine qualities). That’s got to be a byproduct of women’s liberation, right? Well, sort of. But those things are corollary to the movement. The central idea wasn’t “Wear pants and cheat on your husband,” it was “Challenge the idea that your purpose in life is only as good as your reproductive capabilities and maternal instincts.” The Pill was invented. Women started to gain more ground in the workforce. Roe vs. Wade happened. Martha is defeminated insofar as she feels maternity is part of her purpose as a woman, which we are shown, through these recollections of her fake history with her fake son, lies tender beneath Martha’s crass exterior. This defemination causes her to come in contact with the fear that she’s worth nothing if she can’t produce children and raise them and love them. A modern woman would tell Martha she isn’t defined by those capabilities, but re-inventing our self-conceptions are still hard, even if politics is on our side.

The women’s journeys are paralleled by their male counterparts, who also represent two varieties of masculine gender. Nick admits he married Honey for her family’s money and plans on sleeping his way to the top of the university where the two men work. I honestly can’t think of another single piece of media that attaches this Gold Digger Floozy backstory to a male character–but I can think of a good few that attach it to women. So Nick is cast in a feminine light, in a way, by the narrative.

George, meanwhile, gets emasculated over and over by his wife, just as his wife is defeminated by her inability to have children. Martha frequently tells him she “wears the pants” in their household, chastises him for not being man enough to take over the university from her father, curses at him while they’re around Nick and Honey, and even sleeps with another man in their own home. Martha makes George feel the shame she feels by peeling back his masculinity layer by layer. It’s a deflection, and it’s cruel.

But George’s insecurities aren’t examined under the microscope the same way Martha’s are because our culture simply doesn’t tie parenthood to men the way it does to women. Martha’s fear lies in maintaining her sense of self while riding out the turbulence of the women’s liberation movement. Men like George have careers ahead of them, ostensibly. But without motherhood, what is the next step for a woman like Martha? They’ve finally put the fiction of their son to bed–they’ve “killed” him. Martha’s only options now are to conceptualize herself outside of motherhood and child rearing. And that can be quite frightening when that’s the only path you’ve ever been given.