This week for Movie Monday, I’m ranting and raving about one of my favorite topics ever–masculinity and war–with two movies that couldn’t be more different from one another: Lawrence of Arabia and Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love the Bomb.

Lawrence of Arabia is David Lean’s epic four-hour take on the real life of T. E. Lawrence, the man credited for bringing the Arabic tribes together to form the Arab National Council during the crucial takeover of Damascus in World War I. A highly focused, and yet somehow sparse, biopic, Lawrence of Arabia drives the wedge of nuance into the story of T. E. Lawrence, whose history has been muddled by the accounts of the reporter who covered him at the time (Lowell Thomas, emulated in the film in the form of the narrative-seeking Chicago writer Jackson Bently), his fellow service members, his family, and Lawrence’s own autobiography and letters, on which the script is ostensibly based. Peter O’Toole, tall, lithe, and with a face chiseled from a mold God would later use to create Rob Lowe, plays Lawrence as a bright-eyed leader whose mental sanity collapses as he pushes himself further into the horrors of war.

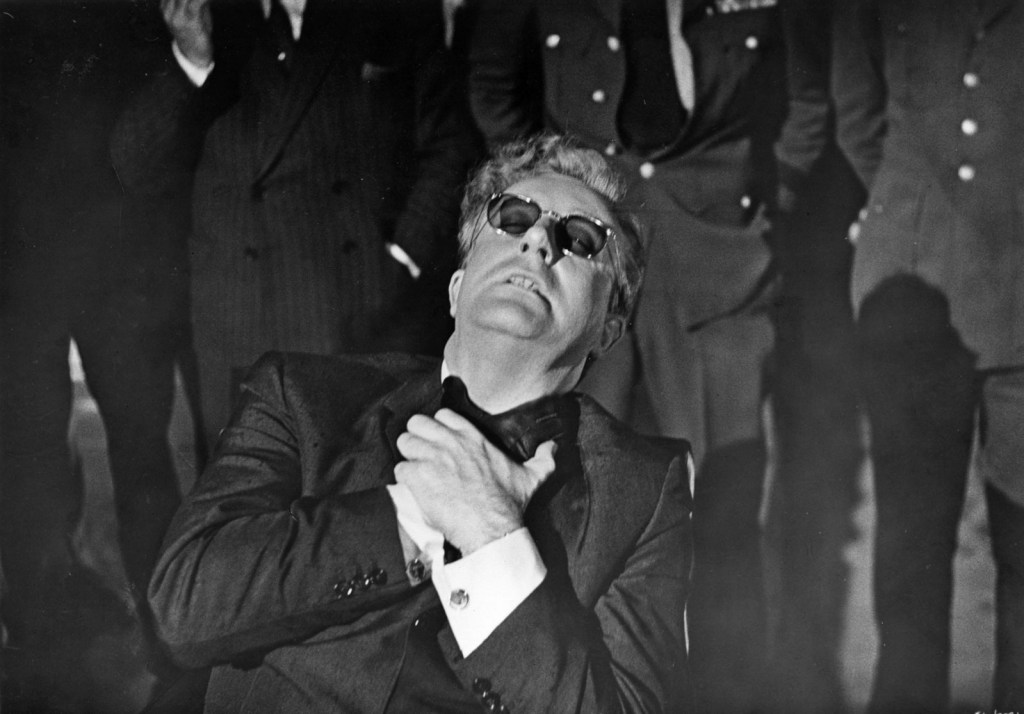

Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love the Bomb, meanwhile, is based on no particular man, but instead satirizes the arms race between the Soviet Union and the United States with sardonic wit. Director, producer, and writer Stanley Kubrick doesn’t allow us to meet the titular character until about a third of the way through the film; yet even then, we know Dr. Strangelove isn’t our protagonist. He might be considered an antagonist, with his suppressed Nazi sympathy creating a sinister presence inside an otherwise well-meaning American government, but in many ways he’s just another face in the ensemble. Except, his face is the most frequent in said ensemble, if only because Peter Sellers plays him and President Merkin Muffley and Group Captain Lionel Mandrake (a creative choice that, I confess, still doesn’t make sense to me). Despite this, the movie resists fixation on one personality and instead shifts between locations and the factions that inhabit them, with hero and villain look-alikes acting at odds with the severity of the situation. The movie is also a tight ninety minutes.

Being the self-serious character study that it is, Lawrence of Arabia seems like a strange match to Dr. Strangelove‘s scramble of darkly comedic mayhem, but the themes of war and masculinity tie them together. I’m not altogether sure that Kubrick or Lean intended to create media that so specifically reflected this connection–or rather, I think Lean was more self-aware about the threads that highlighted masculinity and male power in his material than Kubrick, who chose to highlight war itself more than the personalities of the individual men who fought it. I don’t mean to make statements about either man’s intellect or body of work, but as an overall trend, men often make movies without realizing that masculinity could be a substantial piece of their artistic conversation. Instead, it’s all about “human nature” or our “animal instincts.” But most of these “human nature” hypotheses only take into account a male experience, most likely because the creator himself is male has been historically unlikely to have his worldview challenged.

Take one of the most famous “human nature” books in the canon, Lord of the Flies, for example: In an article titled “Why Lord of the Flies Speaks Volumes About Boys,” novelist Jake Wallis Simons notes that child psychology suggests an all-female plane crash would have gone much differently. Yet, Lord of the Flies is still hailed as a book examining human nature, not masculine nature. Nobody reading this blog right now would doubt that men, particularly white men, are the default characters in mainstream media, which can easily explain why men have a tendency to look at or create things that are about themselves and yet think they’re about everybody. Another tangential example of this can be seen in the clinical blunder of male doctors, who didn’t think it crucial to research how heart attack symptoms might be different in women until a female doctor came along and did the study herself. Thanks to that study, 2013 saw the first decline in deaths for female heart attack patients in decades.

In war movies like Dr. Strangelove or Lawrence of Arabia, which have no women save for the sexed-up secretary in the former and a few dead bodies in the latter, masculinity can’t be avoided as a central theme. War itself is patriarchal, as sociologist and writer Allan G. Johnson explains in his book The Gender Knot: Unraveling Our Patriarchal Legacy. In an excerpt published on his website, Jonson explains this connection by contrasting it to the common myth of soldiers motivated by self-sacrifice:

…war allows men to reaffirm their masculine standing in relation to other men, to act out patriarchal ideals of physical courage and aggression, and to avoid being shamed and ridiculed by other men for refusing to join in the fight. As Keen himself tells us, war is “a heroic way for an individual to make a name for himself” and to “practice heroic virtues.” It is an opportunity for men to bond with other men, friend and foe alike, and to reaffirm their common masculine warrior codes. If war was simply about self-sacrifice in the face of monstrous enemies who threaten men’s loved ones, how do we make sense of the long tradition of respect between wartime enemies, the codes of ‘honor’ that bind them together even as they bomb and devastate civilian populations that consist primarily of women and children?

As Johnson explains here, war serves to preserve masculine ego with the very specific method of violence. Any “respect” is reserved for other men involved and their sacrifice, rather than for the women, children, and civilians they claim to be protecting. (Johnson also makes the very valid point that the individual motivation for signing up for war is different than the sociopolitical reasons war happens, which is worth noting.)

Lawrence, an intellect and oddball, at first seems resistant to the violence of war, but by the midway point of his film has turned a major corner and admits he enjoyed killing a man in cold blood. From then on, he’s shown to be an egoist, posing for photos in white Arab robes atop toppled trains, the bodies of their cars spilling out of the windows, as his forces cheer him on. At one point, possessed by the lust of battle, he charges his forces into a wounded caravan of Turkish soldiers and takes part in the slaughter himself. Later, covered in blood, he regrets this.

Lawrence walks the line between behaving self-aggrandizing and seeming disgusted by the violence that he himself takes part in, yet we see his actions justified time and again by both his superiors in the English ranks, who afford him higher promotions at every turn, and by the deep affections the Arab tribes have for him, culminating in his former-adversary Ali confessing that he loves him (that’s a subject for another post). Lawrence makes a name for himself, bonds with other men, and practices heroic virtues, all in the spirit that war is supposed to inspire in men–and the movie examines textually the cost this has on his soul, and why Lawrence, peculiar and masochistic, keeps returning to it anyways.

Meanwhile, the politicians and generals in Dr. Strangelove struggle to set their egos down long enough to stop the impending nuclear doom. After realizing that the bombers are unlikely to be recalled, the President gets the Russian Premier on the line to give him the coordinates of the planes in hopes that the Premier can shoot them down before they detonate the bombs. The conversation, of which we hear one side, is a comical take on a supposedly serious exchange; at one point the President apologizes for the scandal and a bit ensues where he tries to convince the Premier he’s “just as sorry” as he is. They go back and forth like this for some time, the President’s patiently irritated “Well, Dimitri”‘s ringing ironically in the tense silence. All the while, the Russian ambassador is listening in on a phone that belongs to an American general at the table.

The Russians are treated here with the code of honor that men use to show respect for even their most hated enemies in war. Similarly, the people on the ground are treated as numbers rather than human beings; a general notes at one point that they’ll lose “ten thousand, twenty thousand tops.” And when it seems like a secret doomsday device the Russians have is going to detonate should the American bombers be successful, the Russian ambassador confesses they were going to reveal the device to the world sometime in the coming weeks because the Russian Premier “likes surprises.” By satirizing the frivolity of the politicians and generals controlling the arms race, Kubrick created a movie that points to the way high level decision making is blundered at every turn by the constant skirting around male ego.

Besides this frothy portrayal of war room antics, the arms race itself is a microcosm of war time masculinity, as many sociologists could tell you. Quoted in Sexuality and War, by Evelyn Accord, Bob Connell explains:

The connection between admired masculinity and violent response to threat is a resource that governments can use to mobilise support for war. It has become a matter of urgency for humans as a group to undo the tangle of relationships that sustains the nuclear arms race. Masculinity is part of this tangle. It will not be easy to alter. The pattern of an arms race, i.e. mutual threat, itself helps sustain an aggressive masculinity.

If the arms race is a world-scale my-nuclear-dick-is-bigger-than-your-nuclear-dick fight, then it follows that situating a war satire in the confines of the arms race is to inherently poke fun at the masculinity propelling the arms race forward. But instead of a sympathetic, complex, nuanced portrayal, we get a mockery of the truly fragile egos of war mongers who just want to be treated with respect on the phone. Everything hinges on those codes of honor and Kubrick makes clear that those codes are bullshit from the moment General Ripper takes matters into his own hands (Ripper thinks he’s playing the “protector” role here, by the way).

Johnson actually details an example of the male-protector-pushed-to-violence in his writing, which is quite useful to consider here. He notes:

The heroic male figure of western gunslinging cowboys is almost always portrayed as basically peace-loving and unwilling to use violence “unless he has to.” But the whole point of his heroism and of the story itself is the audience wanting him to ‘have to.’ The spouses, children, territory, honor, and various underdogs who are defended with heroic violence serve as excuses for the violent demonstration of a particular version of patriarchal manhood. They aren’t of central importance, which is why their experience is rarely the focus of attention.

The real interest lies in the male hero and his relation to other men as victor or vanquished, as good guy or bad guy. Indeed, the hero is often the only one who remains intact (or mostly so) at the end of the story. The raped wife, slaughtered family, and ruined community get lost in the shuffle, with only passing attention to their suffering as it echoes across generations and no mention of how they have been used as a foil for patriarchal masculine heroism. Note, however, that when female characters take on such heroic roles, as in Thelma and Louise, the social response is ambivalent if not hostile. Many people complained that the villains in Thelma and Louise made men look bad, but I’ve never heard anyone complain that the villains in male-heroic movies make men look bad. It seems that we have yet another gender double standard: it’s acceptable to portray men as villainous but only if it serves to highlight male heroism.

Movies that feature this heroic male figure are a dime a dozen. I think of various action movies I’ve seen, but also the nerd-vs-jock high school dramas where the friendzoned nerd’s masculinity is only slightly less heinous than the hypermasculinized “cool guy” (spoiler alert: he plays football; in at least one scene the nerd will struggle to lift a very heavy backpack).

Neither Lawrence of Arabia nor Dr. Strangelove glorify the heroic male figure; rather, each is an extremely different take the intersection of war, patriarchy, and masculinity that takes a unique approach. If Dr. Strangelove were a straightforward action film, the heroic male figure might have been the President, who makes tough calls and sacrifices people’s lives for the sake of protecting American citizens, with an ultimate show-down between him and Dr. Strangelove that would assure the American audience that Nazism is never coming back, not on our watch. If Lawrence of Arabia were the throwaway war thriller of the year, Lawrence would have challenged the use of violence until the very end, changing the hearts and minds of British and Arabic troops alike to favor peace over war. He would have brought the Arabic troops together, de-brutalized them, and the Arab United Council would not have dissolved in a day.

But these movies don’t do that, and that’s why they’re special. No, Dr. Strangelove examines the useless egos of wartime politicians and generals, and exposes that when men think their opinions are more valuable than everyone else’s they end up getting people–in fact, everybody–killed. The President, instead of being the powerful patriarch he would have been in a different movie, is undermined by the Nazi scientist who tricks him into believing he’s reformed. Lawrence of Arabia chooses to paint a portrait of a man tortured by doing exactly what he’s supposed to do, which is win a war. He is encouraged by praise from the people of Arabia and by his superiors to continue putting himself in situations of conflict and pain, some of which he enjoys and some of which traumatizes him; though it is lightly handled, none of the trauma is left out, and that’s the point.

Ironically, I think one of the weaknesses is that the films don’t have any women. Most movies about womanhood and femininity feature men in some capacity, whether it’s as husbands and boyfriends or abusers and manipulators or bosses and mentors. The reason this is is because women’s lives do not typically exist with out the presence of men in some capacity, be it at work or at home. But men, especially in the 60s but also today, can go to a place and expect not to see or interact with women. Usually, this is work; sometimes, it is war. In any case, the presence of various genders, when they’re used poignantly, allows for the highlighting of masculinity because there’s something for it to talk to besides just itself.

Maybe that’s the problem with masculinity, patriarchy, and war in general. It’s just a bunch of men talking to each other, without outside perspective. Both Lawrence of Arabia and Dr. Strangelove do portray men in opposition to other men, almost in the vein of Johnson’s villainous-verses-heroic masculine dichotomy, but it does enough work to avoid it the traps of that Hollywood tradition. Mind you, in Lawrence, the Arabic men aren’t always portrayed so generously–the movie was in fact banned in several countries because it was considered racist. And it’s always easy to configure Nazis or Russians as the bad guys when positioning your film to an American audience. Still, each film takes a nuanced punch at what is really going on behind the scenes of war, and how those egos and wills of various men (or types of men) can cause catastrophes as large as nuclear wars or as small as the shattered spirit of the individual.

[…] extrapolate any meaning out of it, which is unusual for me, seeing as I was very charitable towards Dr. Strangelove and it’s depictions of masculinity. I even low key fell in love with Western leads over the […]